In short, we do cross-validation to pick the right model. But what does that mean for our ‘final model’?

Let’s take a step back and motivate the train-test split approach (otherwise known as the evaluation set approach). Like cross-validation, we perform the evaluation set approach because we want to have some idea of how our model performs in the real world.

The evaluation set approach

A simple way to achieve this is to split our data so that the model is *trained* on one part of the data, and *evaluated* on the other part (‘holdout’). This is what we see at the start of most machine learning courses:

In Python, this is what we do when we call train_test_split() from sklearn:

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, 0.3)for R users, using the tidymodels infrastructure, rsample can be used to split training and holdout sets:

library(rsample)

car_split <- initial_split(mtcars)

train_data <- training(car_split)

test_data <- testing(car_split)Training on the evaluation set

Unfortunately for us, in practice, we use the holdout set a lot more than once. Today’s data scientist is spoiled for choice when it comes to algorithms: for gradient boosting alone, you have XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, HistGradientBoosting, gbm etc., not to mention the numerous hyperparameters you have for any one algorithm. If you use the holdout set to guide your choice of hyperparameters, you are bound to overfit on your holdout set.

The no-free-lunch theorem further complicates this problem. Loosely speaking, the no-free-lunch theorem asserts that there is no One True Algorithm that has superior performance across all use cases. Given the above, the data scientist would have to test the algorithm multiple times to see which works best. With the evaluation set approach, this amounts to training on the holdout set.

Another holdout set

If you put this question up to the deep learning folks, they’ll provide you a seemingly simple solution: create two holdout sets. Pick the correct model on Holdout 1 (‘validation’), then evaluate the final model on Holdout 2 (‘holdout’):

This may not be ideal sometimes because:

1. data is often limited: there may not be enough data for two holdout sets. Moreover, in cases where observations are time-sensitive, a TVH approach could reduce the generalizability of the chosen model if the time period of the shrinked training set is less relevant to the problem at hand.

2. Additionally, depending on the observations picked in validation/holdout, test error can be highly variable (see ISLR for details).

K-fold cross-validation

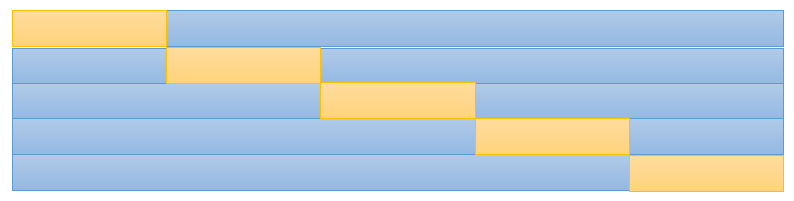

And so we move on to cross-validation, in hopes that we can get around this limited-data problem. This diagram may be familiar to some of you:

In (k-fold) cross-validation, we try to get at some semblance of generalization performance by resampling the development data. Slicing the development data into 5 folds, we train the data on 4 folds, and validate the resulting model on the remaining fold. We repeat this for each permutation of folds, and then average the validation score to obtain the cross-validated score.

Which is the final model?

While performing cross-validation, we have trained K models to evaluate our training procedure. Which should be the final model?

None of the above! The purpose of cross-validation is merely to pick the correct procedure for fitting a model. Whether it be the algorithm or the hyperparameter search space, the purpose of cross-validation is to know what procedure works best for your data. The same procedure can be reused to re-fit the model on new data, and that should make up your final model.

The purpose of cross-validation is model checking, not model building (StackExchange)

In fact, once you’re done with cross-validation and picked your final model, you can, and should, re-train your model-building procedure on all the data you have. There is no reason to drop the holdout set once the optimal procedure has been selected.